Eras in human history are seldom neatly delineated. They tend to be smeared across time in such a way that their beginnings, their pinnacles, and their last gasps are matters of bitter contention. For the sake of brevity then, I shall wind the clock back only to the end of the previous century in order to sketch out the conditions that gave the sixties their character.

[The impatient or busy reader may wish to scroll down quite a way to skip this tiresome preamble and get straight to the amusingly nostalgic videos. I shall think no less of you for it.]

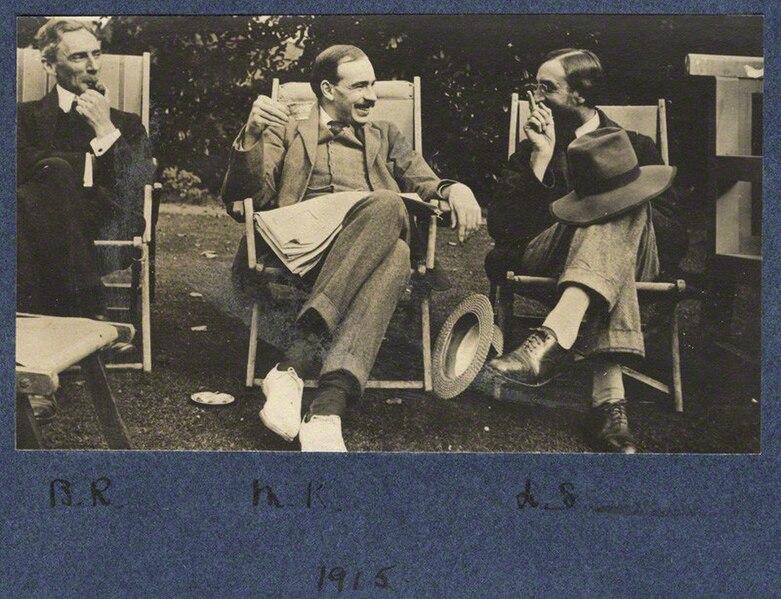

Two of the 20th century's most influential figures, economist John Maynard Keynes, and philosopher Bertrand Russell were products of — and to a great degree reacting against — the Victorian era. Both were members of the Bloomsbury Group and to varying degrees libertine in their personal lives. Both were intellectually rigorous while animated by a deep secular morality. And both prolific, popular, and influential writers of works for a general audience (and often pilloried by their academic peers for so demeaning themselves).

War too figured prominently in the thought of each. Keynes served as a British Treasury official in the negotiations of the Versailles Treaty at the end of the First World War. He walked out in frustration at the viciously punitive war reparations imposed on Germany, warning prophetically that "If we aim deliberately at the impoverishment of Central Europe, vengeance, I dare predict, will not limp. Nothing can then delay for very long that final war between the forces of Reaction and the despairing convulsions of Revolution, before which the horrors of the late German war will fade into nothing."

Yet both were also optimistic about the future, feeling that the principal obstacle to the equitably distributed affluence promised by 20th century technology was simply that of outmoded habits of thought. As Russell put it:

Suppose that, at a given moment, a certain number of people are engaged in the manufacture of pins. They make as many pins as the world needs, working (say) eight hours a day. Someone makes an invention by which the same number of men can make twice as many pins: pins are already so cheap that hardly any more will be bought at a lower price. In a sensible world, everybody concerned in the manufacturing of pins would take to working four hours instead of eight, and everything else would go on as before. But in the actual world this would be thought demoralising. The men still work eight hours, there are too many pins, some employers go bankrupt, and half the men previously concerned in making pins are thrown out of work. There is, in the end, just as much leisure as on the other plan, but half the men are totally idle while half are still overworked. In this way, it is insured that the unavoidable leisure shall cause misery all round instead of being a universal source of happiness. Can anything more insane be imagined?

In Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren (1930), Keynes wrote about the inevitability of dramatically improved productivity (emphasis mine):

Yet there is no country and no people, I think, who can look forward to the age of leisure and of abundance without a dread. For we have been trained too long to strive and not to enjoy. […] I feel sure that with a little more experience we shall use the new-found bounty of nature quite differently from the way in which the rich use it today, and will map out for ourselves a plan of life quite otherwise than theirs.

For many ages to come the old Adam will be so strong in us that everybody will need to do some work if he is to be contented. We shall do more things for ourselves than is usual with the rich today, only too glad to have small duties and tasks and routines. But beyond this, we shall endeavour to spread the bread thin on the butter—to make what work there is still to be done to be as widely shared as possible. Three-hour shifts or a fifteen-hour week may put off the problem for a great while. For three hours a day is quite enough to satisfy the old Adam in most of us!

There are changes in other spheres too which we must expect to come. When the accumulation of wealth is no longer of high social importance, there will be great changes in the code of morals. We shall be able to rid ourselves of many of the pseudo-moral principles which have hag-ridden us for two hundred years, by which we have exalted some of the most distasteful of human qualities into the position of the highest virtues. We shall be able to afford to dare to assess the money-motive at its true value. The love of money as a possession—as distinguished from the love of money as a means to the enjoyments and realities of life—will be recognised for what it is, a somewhat disgusting morbidity, one of those semicriminal, semi-pathological propensities which one hands over with a shudder to the specialists in mental disease. All kinds of social customs and economic practices, affecting the distribution of wealth and of economic rewards and penalties, which we now maintain at all costs, however distasteful and unjust they may be in themselves, because they are tremendously useful in promoting the accumulation of capital, we shall then be free, at last, to discard.

Furthermore, ventured Russell (In Praise of Idleness, 1932), the feasibility of full employment and reduced hours of labour had already been demonstrated in a natural experiment on a vast scale:

The [First World] War showed conclusively that by the scientific organization of production it is possible to keep modern populations in fair comfort on a small part of the working capacity of the modern world. If at the end of the War the scientific organization which had been created in order to liberate men for fighting and munition work had been preserved, and the hours of work had been cut down to four, all would have been well. Instead of that, the old chaos was restored, those whose work was demanded were made to work long hours, and the rest were left to starve as unemployed.

The late (and sorely missed) British parliamentarian and gadfly Tony Benn noticed the same sentiment, widely held, at the end of World War II (at 0:30 in the clip below):

What people said was very simple: in the 1930s we had mass unemployment, but we don't have unemployment during the war. If you can have full employment by killing Germans, why can't you have full employment by building hospitals, building schools, recruiting nurses, recruiting teachers? If you can find money to kill people, you can find money to help people.

The implementation of this reasoning at scale was first realised with the U.S. New Deal programs. In 1933, Keynes wrote an open letter to President Roosevelt offering a mix of praise and constructive criticism:

In a boom, inflation can be caused by allowing unlimited credit to support the excited enthusiasm of business speculators. But in a slump governmental loan expenditure [i.e. what we would now characterise as "deficit spending" — Katy] is the only sure means of obtaining quickly a rising output at rising prices. That is why a war has always caused intense industrial activity. In the past, orthodox finance has regarded a war as the only legitimate excuse for creating employment by government expenditure. You, Mr. President, having cast off such fetters, are free to engage in the interests of peace and prosperity the technique which hitherto has only been allowed to serve the purposes of war and destruction.

However these programs were only envisaged as short-term measures, and reaction against them within the Democratic party led to the ousting of Roosevelt's progressive vice-president Henry Wallace. Wallace was replaced by Harry Truman, who was elevated to the presidency on Roosevelt's death to preside over a government of strikingly different character thenceforth (something to which I'll return, assuming I'm not struck by one of my occasional fits of laziness).

In Britain the Beveridge Report of 1942 envisaged a far more comprehensive and enduring social, economic, and industrial framework, which inspired Australian Prime Minister John Curtin to commission HC. "Nugget" Coombs to produce the White Paper on Full Employment (1945). Coombs' report stated that:

On the average during the twenty years between 1919 and 1939 more than one-tenth of the men and women desiring work were unemployed. In the worst period of the depression well over 25 per cent were left in unproductive idleness. By contrast, during the war no financial or other obstacles have been allowed to prevent the need for extra production being satisfied to the limit of our resources. It is true that war-time full employment has been accompanied by efforts and sacrifices and a curtailment of individual liberties which only the supreme emergency of war could justify; but it has shown up the wastes of unemployment in pre-war years, and it has taught us valuable lessons which we can apply to the problems of peace-time, when full employment must be achieved in ways consistent with a free society.

In peace-time the responsibility of Commonwealth and State Governments is to provide the general framework of a full employment economy, within which the operations of individuals and businesses can be carried on.

Improved nutrition, rural amenities and social services, more houses, factories and other capital equipment and higher standards of living generally are objectives on which we can all agree. Governments can promote the achievement of these objectives to the limit set by available resources.

(Emphasis mine.) In contrast to the preceding "classical", and the subsequent "neo-classical", economic orthodoxy, this post-war Keynesian (indeed arguably Chartalist) interregnum operated on the assumption that the holder of final sovereignty on matters of public policy was the currency-issuing government. Policy was not constrained by the vagaries of the animal spirits of the marketplace, or by some quantity of gold exhumed from one hole in the ground, melted down into bars, and promptly secured behind fortified doors in another hole in the ground. What mattered was the availability of real resources; the labour, raw materials, plant and equipment, etc. which could be brought to bear in solving the problems of the day.

In the wake of a depression deepened and drawn out by austerity policies, and the most devastating war in human history, these problems were considerable, the solutions imperfect, the resources to hand often meager, and the pall of the past cast a long shadow.

My father was not one to dwell on the past, preferring instead to occupy himself with an exhaustive study of the finer points of driving from A to B (for all conceivable values of "A" and "B") at any time, under varying traffic conditions, roadworks, degrees of personal frustration, and so on, the better to proffer expert advice on road navigation whenever he felt it was needed. But he did once draw me aside to describe how my grandmother was so traumatised by the Depression that ever since she still retained curious habits such as washing used tinfoil along with the dishes, drying it, folding it, and putting it away in a drawer for reuse.

In the UK, the rationing of goods which began with the war did not completely end until 1954. The lifestyles of even the well-to-do middle class young were by no means luxurious.

Well into the sixties, the devastation of the war was still apparent, and much of the reconstruction was arguably misguided.

Keynes died in 1946, but Russell outlived the sixties, and as that decade dawned, while not going quite so far as to declare that all you need is love, he averred instead that it's a good 50% of what you need:

As the shadow of the past dispersed, employment and money became less scarce, and assumed strange new forms:

Something seemed to be changing in the culture, although it's expression, even at it's most fantastic, remained stubbornly prosaic.

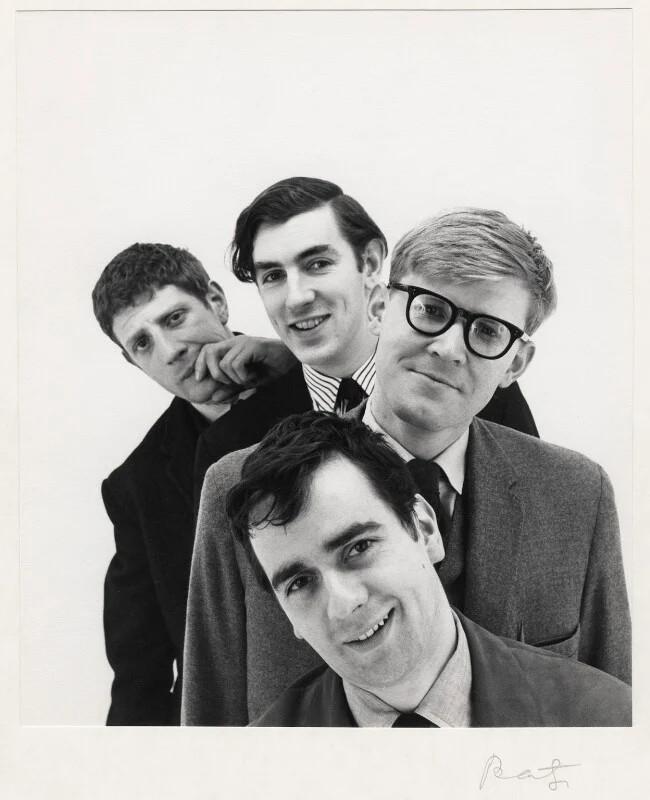

Comedy went from old men in bow ties and cigars telling mother-in-law jokes, to young iconoclasts in skinny ties and drainpipe trousers, feted as though they were rock stars, gleefully puncturing pomposity in the satire boom.

Even Lord Russell failed to escape irreverence:

Of course there was the impending end of the world to contend with as well.

But the music was something else, what with some sort of trans-Atlantic cross-pollination going on, as well as a whole lotta shakin'.

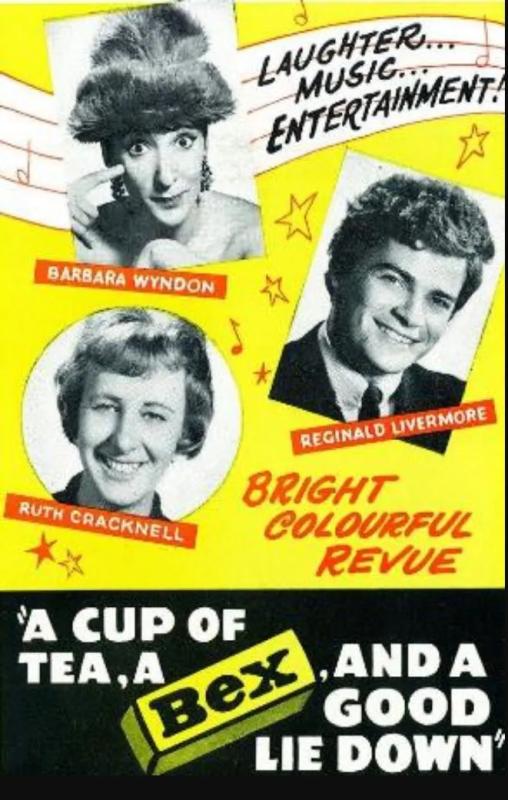

Oh, my. So many nice young men in smart suits! I may need a cup of tea, a Bex, and a good lie down before I go any further.