First, by inking this deal, Coles frames itself as future-forward and logistically driven. Groceries and grocery-store labour become more data, just like the hedge funds, healthcare, or immigrants that other Palantir clients coordinate.

Supermarkets have been under fire over the past year for increasing profit margins through a pandemic and cost-of-living crisis, and accused of underpaying workers.

The Palantir deal continues this extractive trajectory. Rather than paying workers more or passing savings onto customers, Coles has chosen to invest millions in technology that will “address workforce-related spend” as part of a larger effort to cut costs by a billion dollars over the next four years. Food (and the labour needed to grow, pack and ship it) is transformed from a human need to an optimisation problem.

Second, dependence. As my own research found, Palantir clients tend to enjoy the all-encompassing data and new features but also become dependent on them. Data mounts up; new servers are needed; licensing fees are high but must be paid.

Much like Apple or Amazon, Palantir’s services excel at creating “vendor lock-in”, a perfect walled garden which clients find hard to leave. This pattern suggests that, over the next three years, Coles will increasingly depend on Silicon Valley technology to understand and manage its own business. A company that sells a quarter of Australia’s groceries may become operationally reliant on a US tech titan.

In The Conversation

Solving the supermarket: why Coles just hired US defence contractor Palantir

in The ConversationAustralia spends $714 per person on roads every year – but just 90 cents goes to walking, wheeling and cycling

in The ConversationEven if you don’t want to walk, wheel or ride, you should care because less driving helps everyone, including other drivers, who benefit from reduced traffic.

As a result of this over-investment in car road-building, Australia has the smallest number of walking trips of 15 comparable countries across Western Europe and North America.

Cycling rates are equally dismal.

Globally, the United Nations recommends nations spend 20% of their transport budgets on walking and cycling infrastructure.

Countries like France, Scotland, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden and the largest cities in China invest between 10% and 20%.

These places were not always known for walking and cycling – it took sustained redirecting of investment from roads to walking and cycling.

Meanwhile, many Australians are dependent on cars because they have no other choice in terms of transport options.

Australia’s drama dilemma: how taxpayers foot the bill for content that ends up locked behind paywalls

in The ConversationHeadlines about Screen Australia’s latest annual Drama Report have highlighted one particular figure: a 29% drop in total industry expenditure compared to the year before.

But a closer look suggests this isn’t the most concerning finding. The report also reveals a significant chunk (42%) of the A$803 million spent on producing Australian TV drama in 2023–24 was funded by taxpayers.

What’s more – watching half of the Australian TV drama hours broadcast in 2024 required a streaming subscription. Watching all of them required seven different subscriptions.

With Australians’ funding of this commercial, for-profit sector on the rise, we can’t help but ask: what do Australian viewers get in return?

Knowing less about AI makes people more open to having it in their lives – new research

in The ConversationFrom the authors of "People Who Don't Understand Magic Trick More Likely To Be Impressed By It".

People with less knowledge about AI are actually more open to using the technology. We call this difference in adoption propensity the “lower literacy-higher receptivity” link.

This link shows up across different groups, settings and even countries. For instance, our analysis of data from market research company Ipsos spanning 27 countries reveals that people in nations with lower average AI literacy are more receptive towards AI adoption than those in nations with higher literacy.

Similarly, our survey of US undergraduate students finds that those with less understanding of AI are more likely to indicate using it for tasks like academic assignments.

Achieving net zero with renewables or nuclear means rebuilding the hollowed-out public service after decades of cuts

in The ConversationWhether it’s Labor working to get transmission lines and offshore wind up and running or the Coalition working to create a nuclear industry from scratch, it will take a strong government with the capacity to articulate a plan, and the legal, financial and human resources to make it a reality.

All of these requirements were met when we constructed the Snowy Mountains Scheme, a decades-long federal government initiative undertaken in cooperation with Victoria and NSW.

Are they still in place? Not yet. Government capacity to act has been eroded over decades of neoliberalism. Particularly at the national level, public service expertise has been hollowed out and replaced by reliance on private consulting firms.

To rebuild the federal government’s capacity to act will require recreating the public service as a career which attracts the best and brightest graduates – many of whom currently end up in the financial sector.

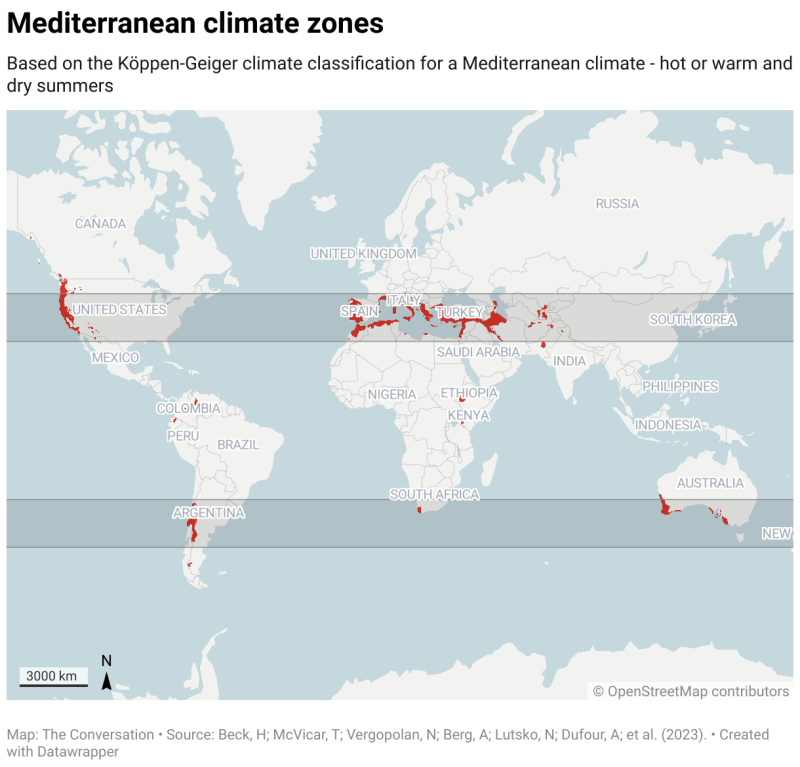

Much of Australia enjoys the same Mediterranean climate as LA. When it comes to bushfires, that doesn’t bode well

in The ConversationAs global temperatures increase, Earth’s water cycle is changing. Over the past 50 years, this has led to an expansion of Earth’s tropical and subtropical zones. Tropical areas are moist and lush, but dry at the northern and southern edges.

These dry edges are pushing towards the poles. Regions that used to enjoy a gentler Mediterranean climate, as shown in the map below, are turning into dry subtropical zones.

They include highly populated regions, such as Southern California. Similarly, parts of Australia including Perth and much of southeast Australia has dried in recent decades, in a pattern consistent with tropical expansion.

Why being forced to precisely follow a curriculum harms teachers and students

in The ConversationIn a recent study, I interviewed 12 teachers, primarily in rural towns in the Northeast, about how they deal with problems that arise in the classroom every day. They discussed how they came up with responses based on best practices they had learned in school from resources such as books and videos. They also spoke of techniques they learned in professional development workshops.

Of the nine who worked in public schools or publicly funded child care centers, however, all but one of the teachers were influenced by pressure to follow a curriculum to fidelity. This pressure came from administrators in the form of threats of punishments and even job loss, as well as from colleagues who questioned when they taught a curriculum differently.

[…]

The term “fidelity” comes from the sciences and refers to the precise execution of a protocol in an experiment to ensure results are reliable. However, a classroom is not a lab, and students are not experiments.

As a result, teachers and teacher educators have long decried fidelity and the impact it has on them and their students.

One participant in my study, a fourth grade public school teacher, described an oppressive environment at her school: “They were really driving the curriculum down our throats. We need to meet this at this date. And everyone should be at this lesson at this date.”

This counteracted what she was taught in college – every student is different, and every classroom is different. Not all teachers will be on the same lesson on the same day.

Researchers of tobacco, alcohol and ultra-processed foods face threats and intimidation – new study

in The ConversationWe mapped the extent to which researchers and advocates have been subject to intimidation tactics by tobacco, alcohol and ultra-processed food (UPF) companies and their associates. The tactics described include being descredited in public, legal threats, complaints, nefarious use of Freedom of Information legislation, surveillance, cyberattacks, bribery and even physical violence.

[…]

The scale of intimidation we have found is likely to be the tip of the iceberg. Many will be too scared to publicly reveal that they have been intimidated because of their work.

We found widespread intimidation across the three sectors, perpetrated by corporations themselves and their third parties. In the most serious forms of intimidation, the perpetrators remained unknown.

NZ is consulting the public on regulations for puberty blockers – this should be a medical decision not a political one

in The ConversationPuberty blockers delay the onset of puberty, but don’t necessarily result in a measurable effect at the time they are taken. The main impact is seen when people are older. The physical effects of a puberty that does not match a person’s gender can have serious negative consequences for transgender adults.

In my role as a GP, I regularly hear from transgender adults (who have not had puberty blockers) struggling with distress related to bodily changes which occurred during puberty.

I have met people who don’t speak because their deep voice causes others to make incorrect assumptions about their gender. Some harm themselves or avoid leaving the house because of the distress caused by their breasts. Others seek costly surgical treatments.

This is when the benefits of maintaining equitable access to puberty blockers for those who need them become obvious. People are seeking hormones, surgery and mental health support for changes which could have been prevented by using puberty blockers when they were younger.

The ministry’s position statement recommends that puberty blockers are prescribed by health professionals who have expertise in this area, with input from interdisciplinary colleagues.

In my experience this describes how puberty blockers are currently being prescribed in New Zealand. Clinicians are already cautious in their prescribing. They work with multidisciplinary input to best support the young person and their family. They recognise the importance of mental health and family support for young people.

How long should everyday appliances last? Why NZ needs a minimum product lifespan law

in The ConversationThe Consumer Guarantees (Right to Repair) Amendment Bill now before parliament offers some hope. It builds on the Ministry for the Environment’s 2021 consultation document, “Taking responsibility for our waste”.

The bill seeks to force manufacturers to provide spare parts, repair information, software and tools to consumers for a reasonable period after the sale of goods. But there is still too much doubt about how long those goods and parts should last in the first place.

To give manufacturers and consumers more certainty, establishing minimum product lifespans is essential. This would be defined as the period for which a product can perform its intended function effectively.

Repairs can extend this functional lifespan. So it is also important to factor in a “repairability period” when products can be repaired at the consumer’s expense, beyond the manufacturer’s implied or expressed guarantee. Spare parts, repair information and necessary tools must be made available.

[…]

Planned obsolescence can involve integrating components that are likely to fail sooner than the product itself, withholding spare parts, or requiring prohibitive information and proprietary tools for repairs.

Ultimately, it is about maximising profitability, and extends from smartphones and appliances to automobiles and farm machinery. It fosters a throwaway culture, adding to the strain on waste systems and landfills.