Restoring Our Republican Way of Life

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —Everyone remembers the famous warning Benjamin Franklin reportedly gave Elizabeth Willing Powel as he and his fellow framers left the Constitutional Convention’s final session: they’d created “a republic, if you can keep it.” What’s less understood is that we didn’t.

Ronald J. Pestritto’s new Provocation from the Center for the American Way of Life brings the welcome news that valiant efforts have begun to restore the lost republican framework that those great men designed. But since most Americans believe we still live under the regime forged in Philadelphia, what’s equally valuable in Pestritto’s essay is his lucid reminder of just how we squandered the brilliant contrivance that James Madison shepherded through the Convention: the self-governing republic formed, as Alexander Hamilton wrote, by “reflection and choice” rather than by “accident and force,” arguably the finest achievement of the Western Enlightenment.

The “Donroe Doctrine” In Action

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —The Trump Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine was barely a month old when the president ran a successful one-hour military operation, with no American casualties, that captured Venezuelan strongman Nicolás Maduro.

Most of the responses thus far have been one-dimensional, for better or worse: “Trump grabbed a wanted narcoterrorist cartel leader to stand trial.” “He’s starting another war for oil to help his capitalist cronies.” “He’s getting us into another war of choice.” “He’s betrayed his base and done a regime change as a tool of the (insert hidden hand here).” These arguments are simple and easy to understand. They range from the politically and legally tidy to stale anti-imperialist Marxism and paranoid isolationism, which often sound like the same thing, to the ragebait trolling of the gullible. But they all fail to understand the full gravity of the administration’s accomplishment in Venezuela.

In capturing Maduro, Trump has removed a key pillar that, if played wisely, could compromise the web of entangling alliances of many of our most dangerous adversaries.

Operation Absolute Resolve, paralleling the collapse of the Islamic Republic of Iran, just might have forestalled Communist China’s expected invasion of Taiwan. The synchronicity is perfect. Maduro joins Iran’s mullahs in a pas de deux to the bottom, while the Cuban Communist regime, constantly suckling at a wealthy patron’s teat for 65 years, now faces a fatal weaning.

Modern slavery in Australia? | PALMed Off, Episode 1

— Organisation: The Australia Institute —In PALMed Off, a special series of Follow the Money, we explore the Pacific Australia Labour Mobility (PALM) scheme, a program that allows people from nine Pacific Island nations and Timor Leste to work in Australia on a special temporary visa. The Australian Government argues the program is a win for the workers, their home communities and Australian employers. But PALM visa holders are subjected to restrictions that no other worker in Australia – temporary or permanent – have to put up with, and this has led to concerns that the program is facilitating modern slavery in Australia.

In the first episode of this four-part series, host Morgan Harrington speaks with people from Vanuatu who have worked in Australia under the PALM scheme and considers what it really means for Australia’s relationships with Pacific Island nations.

The interviews for this podcast were recorded between June and August 2025.

Host: Morgan Harrington, Research Manager, The Australia Institute // @mhharrington

Interviewees: Enoch Takaua (ecotourism business operator), Thomas Costa (Unions NSW), Dr James Cockayne (NSW Anti-slavery Commissioner), (Waskam) Emelda Davis (ASSI-Port Jackson Chair), Dr Matt Withers (ANU), Murielle Meltenoven (Commissioner, Vanuatu Department of Labour & Employment Services), anonymous former PALM workers

Editorial — From the Ashes? | Special Issue – Winter 2026

— Publication: Perspectives Journal —- 2025 Federal Election Assessments and Observations – Luke Savage

- The Protean Politics of Social Democracy: New Democrats at a Crossroads? – Bryan Evans & Matt Fodor

- Narrativizing Confidence and Supply: NDP Political Communications during the Supply-and-Confidence Agreement – Dónal Gill & Ryan Mohtajolfazl

- The Changing Class Basis of Canadian and Social Democratic Futures – Matthew Polacko, Peter Graefe & Simon Kiss

- A Social Democratic Canadian Foreign Policy – Jennifer Pedersen & Simon Black

- Labour and the NDP: Revisiting the Past, Looking to the Future – Larry Savage

- OPINION: NDP Leadership Race Should Look to History on How to Change Canada – Clement Nocos & Dave McGrane

Which Entrepreneurs Boost Productivity?

— Organisation: Federal Reserve Bank of New York — Publication: Liberty Street Economics —America the Rogue State

— —A Social Democratic Canadian Foreign Policy

— Publication: Perspectives Journal —Introduction

As the post-Second World War liberal international order gives way to a right-wing reactionary internationalism, the task of reimagining social democratic foreign policy and a progressive internationalism is more urgent than ever.

Canadian socialists have certainly experienced a different foreign policy trajectory than contemporary left-wing and centre-left parties around the world. While today’s German SDP takes a zeitenwende towards increased militarism, reacting to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, left-wing governments in Latin America, such as Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Mexico, and Uruguay look to a new multilateralism. Through this multilateralism, countries in the Global South have demanded respect for international law in the ongoing genocide in Palestine, but Canada’s foreign policymakers have lagged as they scramble to figure out their continued dependency on a far-right US government.

Narrativizing Confidence and Supply: NDP Political Communications during the Supply-and-Confidence Agreement

— Publication: Perspectives Journal —The 2022 Parliamentary Supply-and-Confidence Agreement (SACA) between Justin Trudeau’s Liberal minority government and the New Democratic Party (NDP) under the leadership of Jagmeet Singh was a watershed moment for Canada’s social democratic party. The party entered the agreement with two strategic goals: (1) to implement legislation aligned with its ideological agenda, and (2) to present itself as a “legible alternative” (Massé & Beland 2024, 499) to the governing Liberals on the progressive side of Canadian politics. However, the political communications deployed by Singh during the SACA was marked by incoherence, undermining the NDP’s legibility as a viable left-wing governing option. The 2025 federal election results confirm the agreement’s electoral failure: the NDP won only 7 seats with 6.3 percent of the vote.

2025 Federal Election Assessments and Observations

— Publication: Perspectives Journal —Introduction

Canada’s 2025 federal election delivered a painful result for the New Democratic Party. Entering the campaign with 24 seats, the NDP ultimately won just 7 and lost Official Party status in the House of Commons for the first time since 1993. What accounts for this outcome and could it have been avoided? How does it compare to other electoral ebbs throughout the party’s history? What are the NDP’s prospects, and to what extent does the 2025 result risk consolidating a US-style duopoly between Conservative and Liberal parties for Canadian federal politics in the longer term? With these and other related questions in mind, this essay will offer a broad assessment of the 2025 federal election and its aftermath, and several more general observations about the NDP. As the party conducts its leadership race and debates the path forward, my modest aim for this assessment is to engage some of the key issues and questions raised by the 2025 NDP campaign, beginning with a broad survey of the election itself.

Securing the Nation

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —Today, the concept of “national security” is a staple of our political vocabulary, common in everyday language and entrenched in official institutions such as the National Security Council. But it was not always thus. Total Defense by Andrew Preston, a Canadian who is now a history professor at the University of Virginia after nearly 20 years on the faculty of Cambridge University, traces the rise of this concept and how it displaced earlier notions of national defense during the course of the 20th century. It is an important history, and one with underappreciated implications.

The book’s subtitle—The New Deal and the Invention of National Security—distills its thesis: the concept of national security as we know it today (involving military and foreign policy matters not limited to territorial defense) coalesced during the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt. Before the New Deal era, “national security” was used relatively rarely, and often to refer to something more like economic and political stability or, in the 19th century, national unity versus sectional interests. But in the 20th century, a new vocabulary was required to grapple with increasingly grave foreign threats that did not involve the imminent invasion of U.S. territory. Such a vocabulary was largely lacking in World War I, but the term “national security” emerged in the years leading up to World War II.

What were the big wins and losses of 2025?

— Publication: Advancing Learning and Innovation on Gender Norms (ALIGN) —The Enduring Quest for Self-Government

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —We no longer live in a republican regime, properly speaking. We are instead governed by a class of administrators whose claim to rule is based on expertise rather than the consent of the governed. As Ronald J. Pestritto argues, President Trump’s administration has embarked “on the most extensive project since at least the 1930s to reclaim executive power from unelected bureaucrats and judges.” It’s hard to disagree with Pestritto’s observation that, in a more constitutionally sound world, we would not have to rely on the executive branch alone to do this heavy lifting. But as the saying goes, here we are. Whatever one might think of the current occupant of the White House, he is elected by the people—which is more than can be said of federal bureaucrats and judges. Ironically, those who complain most loudly about assaults on “our democracy” are least committed to restoring it.

Panel Lines

— —Foreword: This is not a typical Stained Glass Woman article.

While it talks about a few identities that are much more common among trans people than they are in the general public, it is not, directly, about anything to do with being trans.

Labour and the NDP: Revisiting the Past, Looking to the Future

— Publication: Perspectives Journal —While the Federal New Democratic Party could never rely on a majority of union members’ votes, that support now appears as elusive as ever. Indeed, formal ties between the NDP and the labour movement are considerably weaker than they were at the time of the party’s birth in 1961. The crisis of social democratic electoralism, the impact of campaign finance reform, and ongoing concerns about the party’s electoral viability have all contributed to a weakening of the union-party link.

However, the loosening of ties between labour and the NDP has not shifted the landscape of labour politics in the direction of a more left-wing brand of working-class politics as some on the labour left had hoped. Rather, the opposite has occurred, as evidenced by the clear emergence of fair-weather and transactional alliances with Liberals and Conservatives as the main alternative to traditional partisan NDP links in the realm of electoral politics.

History and Institutional Links

When the NDP was founded in 1961, it was heralded as the political voice of Canada’s labour movement. Born from a partnership between the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) and the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), the party’s architects envisioned the NDP would realign Canadian politics along a left-right axis and unite workers under a single political banner. Yet, despite the initial fanfare, the relationship between the NDP and unions was never as strong as many assumed—and in recent years, it has only grown weaker.

The Changing Class Basis of Canadian and Social Democratic Futures

— Publication: Perspectives Journal —Introduction

The international conversation about social democracy is quite focused on electoral sociology: What blocks of voters support social democratic parties? Can parties craft new electoral coalitions between the working-class, public-sector workers and even professionals? Do these coalitions undermine the parties’ commitment to economic redistribution by favouring more middle-class issues?

The conversation about social democracy in Canada has had much less to say about which voting blocs or electoral coalitions the NDP is pursuing or ought to pursue. After the near complete desertion of its electorate in the 2025 election, it is crucial to ask what coalition of supporters the federal NDP has been able to attract over the past couple of decades, what challengers it faces in retaining those supporters, and what tensions exist within that coalition. We pay particular attention to working class voters. They have historically been an important voting bloc for the NDP. The supposed desertion of the working class from the NDP to the Conservatives has also been an effective trope for political opponents making the case for the NDP’s loss of relevance.

The discussion below draws on a number of recent analyses we have conducted on the relationship of socio-economic class to voting behaviour in Canada over the past half century, relying on the Canadian Election Study. We emphasize that the NDP has some cards to play to reconnect with working class voters, especially around redistribution and economic populism.

The Protean Politics of Social Democracy: New Democrats at a Crossroads?

— Publication: Perspectives Journal —This special edition of Perspectives Journal poses the question: “Canadian social democracy at a crossroads?” This framing suggests only presently has Canadian social democracy arrived at such a fork in the road. Yet the history of other social democratic parties in the Global North, including that of the CCF-NDP, points to other periods where other forks in the road appeared, and consequential political choices made. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, socialist and labour parties were established around the world with the goal of the socialist transformation of society. Throughout the latter 20th century, this transformative vision largely disappeared. Social democratic political parties that survived during this period no longer sought the whole transformation of society and instead pursued a pragmatic management of capitalism. The consequence for social democracy, in changing its pursuits, has become the contemporary decline in working-class support, declining leadership and representation of people from working-class backgrounds, and the weakening of once firm relationships with trade unions. (Rennwald 2020, 3). The CCF-NDP historical experience is not unique among these global historical trends for social democracy.

America is a Gangster State

— —Media Release: Join the march against genocide and Albanese’s invitation to Israeli President to visit Australia

— Organisation: Free Palestine Melbourne —Media Report 2025.12.30

— Organisation: Free Palestine Melbourne —Recommended article: The service sector path to shared prosperity

— Organisation: Economic Reform Australia (ERA) —Recommended article: The service sector path to shared prosperity [1] Dani Rodrik We must address climate change, inequality, and poverty simultaneously, but prevailing economic approaches…

The post Recommended article: The service sector path to shared prosperity appeared first on Economic Reform Australia.

A post-Keynesian discussion of US economic hegemony: resilience or decline? (Part 1)

— Organisation: Economic Reform Australia (ERA) —A post-Keynesian discussion of US economic hegemony: resilience or decline? (Part 1) Alan Prout Introduction Since 1945 the USA has, at least until recently, been…

The post A post-Keynesian discussion of US economic hegemony: resilience or decline? (Part 1) appeared first on Economic Reform Australia.

From public good to corporate enterprise: The financialisation of universities (Part 2)

— Organisation: Economic Reform Australia (ERA) —From public good to corporate enterprise: The financialisation of universities (Part 2) John H Howard A dominant challenge for universities now is the expectation that…

The post From public good to corporate enterprise: The financialisation of universities (Part 2) appeared first on Economic Reform Australia.

From neoclassical economics to the masking of it with New-Keynesian economics

— Organisation: Economic Reform Australia (ERA) —From neoclassical economics to the masking of it with New-Keynesian economics Tyrone Keynes Economists often begin by making assumptions that bear little resemblance to reality.…

The post From neoclassical economics to the masking of it with New-Keynesian economics appeared first on Economic Reform Australia.

What caused both the Great Depression and the 2008 crisis?

— Organisation: Economic Reform Australia (ERA) —What caused both the Great Depression and the 2008 crisis? Steve Keen Mainstream economists completely missed what caused both the Great Depression and the 2008…

The post What caused both the Great Depression and the 2008 crisis? appeared first on Economic Reform Australia.

How to talk about it

— Organisation: Economic Reform Australia (ERA) —How to talk about it John Alt Framing MMT as a Part of Normative Society Zohran Mamdani [1] will soon be asked the question: How…

The post How to talk about it appeared first on Economic Reform Australia.

The China dependency nobody talks about

— Organisation: Economic Reform Australia (ERA) —The China dependency nobody talks about: How smart countries build dumb export structures Darren Quinn Part 4 of my series on vulnerability-based monetary sovereignty Here’s…

The post The China dependency nobody talks about appeared first on Economic Reform Australia.

Economic myths

— Organisation: Economic Reform Australia (ERA) —Economic myths Mark Diesendorf The dominant economic system, capitalism, has the goal of generating profit through private ownership and control of the means of production.…

The post Economic myths appeared first on Economic Reform Australia.

The Trillion Dollar War Machine (w/ William D. Hartung) | The Chris Hedges Report

— —This interview is also available on podcast platforms and Rumble.

The military-industrial-complex (MIC) is unique in its ability to pull untold flows of tax revenue into “defensive” infrastructure that benefits no one other than the private sector manufacturing and investing in it. The machine, which perpetuates itself through an incestuous milieu that lobbies for war and defense spending, wages psychological warfare on citizens and engages in corrupt backroom deals, has risen to once unthinkable heights of influence and power since Dwight D. Eisenhower first warned Americans of its growing presence in 1961.

A just transition can remake Australia if we choose to think bigger

— Organisation: Economic Reform Australia (ERA) —A just transition can remake Australia if we choose to think bigger Peter Hansford A “just energy transition” seeks to balance risks and benefits fairly,…

The post A just transition can remake Australia if we choose to think bigger appeared first on Economic Reform Australia.

The confident falsehoods of economists and the Nobel Prize

— Organisation: Economic Reform Australia (ERA) —The confident falsehoods of economists and the Nobel Prize Lars Syll Faced with economic theory’s apparent inability to address real economic and financial problems, economists…

The post The confident falsehoods of economists and the Nobel Prize appeared first on Economic Reform Australia.

Review of Southern Interregnum

— Publication: Progress in Political Economy —Southern Interregnum: Remaking Hegemony in Brazil, India, China, and South Africa offers a timely account of what the authors argue is an ongoing conjunctural crisis in the global South whereby governing elites are struggling to reconcile the imperatives of accumulation and legitimation.

Ben Bernanke — the “expert” who got it all wrong

— Organisation: Economic Reform Australia (ERA) —Ben Bernanke — the “expert” who got it all wrong Extracted from an article by Steve Keen [1] Ben Bernanke got the job as Federal…

The post Ben Bernanke — the “expert” who got it all wrong appeared first on Economic Reform Australia.

2025 is ending, my mom is in the ICU

— —Last year at this time, I posted my 2024 annual wrap-up.

This year, I was planning to do this same.

Instead, I want to take a minute to acknowledge this newsletter’s first and greatest supporter, the person who has encouraged and praised my writing since I was 6 years old, and who has masked and protected me from COVID reinfections without protest: my mom.

Her birthday is Christmas Day, and this Christmas she turned 73.

While I was growing up, she always insisted that we carefully identify which presents were “Christmas” presents and which were “birthday” presents- ensuring that no one used the date as an excuse to skimp out.

Unfortunately, three days before Christmas (and her birthday), my mom had a bad fall on the stairs in our family home. She had previously been diagnosed with Parkinson’s dementia, which likely led to her fall.

Since then, she has been in the ICU. She has bleeding in the brain which has been ongoing for a week. We are unsure whether she will recover, but desperately hoping that she will.

I have been unable to travel to my mom’s bedside since I’m homebound and largely bedbound with Long COVID in DC, and my parents live in Pittsburgh. I cannot drive anymore, nor am I well enough to fly.

The Real Watergate Scandal

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —The United States Constitution establishes a republic, not a monarchy. If an American president ever had royalist or autocratic aspirations, it would pose an existential threat to the Constitution. Numerous Americans believe that’s what made President Richard Nixon so dangerous. When House Speaker Carl Albert denounced Nixon’s “one‐man rule” in 1973, he was channeling the opinion of many at the time—and since. But removing a monarch from office is no smooth, straightforward affair. If it’s true that Nixon acted like a king, then the closest the country has ever come to regicide was the drama of Watergate. The scandal began with the arrest on June 17, 1972 of five men working for the Republican Committee for the Re-Election of the President (CRP), who were caught breaking into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee, located in the Watergate Office Building. The scandal appeared to end with Nixon’s resignation speech two years later, on August 8, 1974. The successful removal of the president took presidential authority down in its wake, condemning any president who tries to recover it as another Nixon, another monarch-in-the-making. This has itself become a scandal, a stumbling block to understanding some of the most tumultuous years in American history, when the country and its politics changed forever.

Only Real Masculinity Can Overcome Groyperism

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —Nick Fuentes is a problem. His influence is growing, fueled by his deft channeling of valid grievances. He has been further buoyed by neoconservatives and the progressive Left, both of which are desperate for “Nazi” bogeymen to validate their anti-MAGA hysterics. However, their ritual denunciations of Fuentes and his groyper legions are worse than useless. They merely encourage groyperism by providing a bigger kick of frisson due to breaking social taboos.

Chris Rufo argues that Fuentes’s critics misapprehend the groyper phenomenon by taking it in earnest instead of recognizing the “hyperreal” run amok. The French sociologist Jean Baudrillard used the term to denote the condition of postmodernity wherein our representations of reality become more phenomenologically real to us than reality itself, until they detach from reality entirely. “Emptied out, [signs] then circulate through digital media,” writes Rufo, “where they drive the discourse and, while purely derivative, still spark real emotional involvement.”

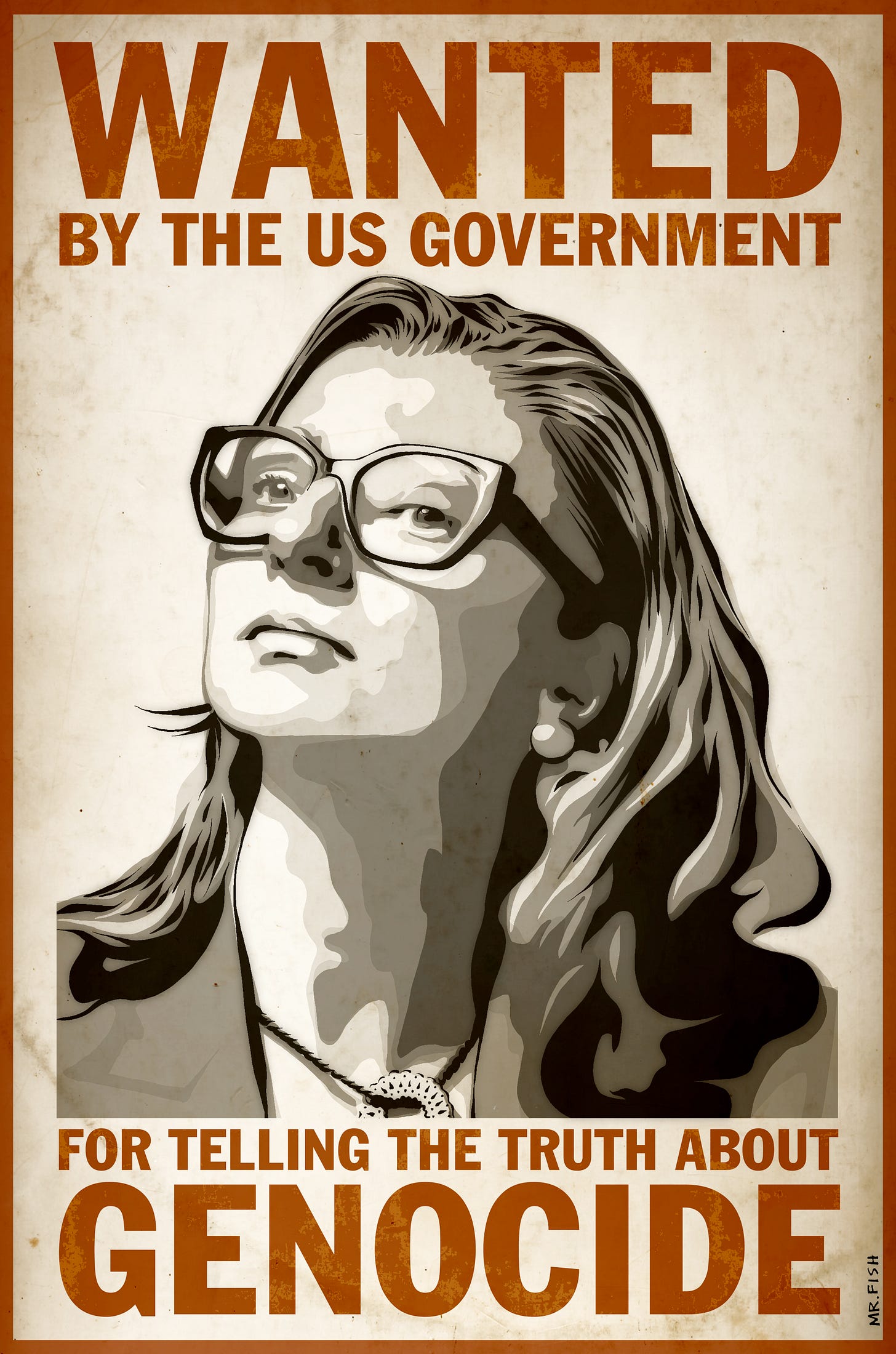

Francesca Albanese and the Lonely Road of Defiance

— —How Republicans Can Win Gen Z Women

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —Gen Z women, the most liberal demographic in the country, are becoming a powerful share of the electorate. Yet conservatives are misreading what actually drives our political decisions. While the legacy media fixates on a supposed surge of right-leaning youth, the reality is more complicated. Young women are not moving right because Republicans keep repeating the same mistakes Democrats made with young voters in the last election cycle.

Last year, I wrote about former presidential hopeful Kamala Harris’s failed attempt at being hip with the cool girls during her 2024 campaign. During a year when women were suffering sexual violence in conflicts from Gaza to Ukraine, and when the prospect of marriage and family felt economically out of reach, Harris had countless opportunities to show young women she understood our concerns. Instead, she fixated on the fact that British musician Charli XCX made a pop culture reference about her, invited social media influencers to the Democratic National Convention, and appeared on a sex podcast while Americans were dying in a hurricane. Harris’s endeavor to win over the youth was more than wildly unsuccessful. It was vapid, unserious, and embarrassing. It communicated a belief that young women’s concerns begin and end with oversexed pop culture.

This Briley Parkway Cop Fight Is the Gift That Keeps On Giving

— —Novel Reading in 2025

— Publication: Progress in Political Economy —Following my annual practice, I have listed here my “novel” reading for 2025. This is a way of documenting what I get through in a year’s worth of reading on the commute to work, in the evenings after work, and while travelling outside of my “normal” academic reading. My use of the term “novel” reading is loosely adopted, as you will see from the list to include fiction and then really important non-fiction work I get excited to read in my spare time. As you will see, my novel reading shifted away from novels to much more academic reading in my “free time” and then back again. But that approach has been richly rewarding.

This year my imagination was captured by Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall Trilogy, a choice inspired by old school friend Mike (“Sarge”) Denson, who is still educating me now as much as he did back when we were teenagers. Aside from reading, Mantel’s core rule for writing is “show up at the desk”, which is pretty much relevant to us all as writers of whatever form.

Revisiting Issues of Affordability, Income and Inequality

— —This post updates my previous writings on how inequality data based solely on income ignores housing tenure, wealth and social transfers in kind. This fundamentally misunderstands hardship and inequality and leads to poor policy.

The post Revisiting Issues of Affordability, Income and Inequality appeared first on Greg Ogle's After Dinner Political Economy.

The American Mind Podcast: The Roundtable Christmas

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —The American Mind’s ‘Editorial Roundtable’ podcast is a weekly conversation with Ryan Williams, Spencer Klavan, and Mike Sabo devoted to uncovering the ideas and principles that drive American political life. Stream here or download from your favorite podcast host.

We Wish You a Merry Christmas | The Roundtable

This week, hosts Ryan and Spencer sit down as the year closes out to share their Christmas plans and recommendations: music, theater, food, drink, and more! Stay tuned in the new year!

How the 'Epstein Class' Fails to the Top | The Chris Hedges Report (w/ Anand Giridharadas)

— —This interview is also available on podcast platforms and Rumble.

Noam Chomsky once said “The more privilege you have, the more opportunity you have. The more opportunity you have, the more responsibility you have.”

Today, this profound quote from an important figure is ensconced in irony, not only in light of Chomsky’s close ties with Jeffrey Epstein, but also regarding the entire ruling class structure’s facilitation of the pedophile’s rise to the top. Anand Giridharadas, in his book Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World, talks about this privilege and the elite delusions that capitalism and capitalists can save the planet from the very problems that they create.

Tariffs, Trade, and Tumbling Credit Scores: The Top 5 LSE Posts of 2025

— Organisation: Federal Reserve Bank of New York — Publication: Liberty Street Economics —

Each year brings a new set of economic challenges: In 2025, major areas of focus included tariffs and trade tensions, as well as the financial pressures facing younger adults. New York Fed economists contributed insightful research on both topics—and readers took notice. In fact, all five of the year’s most-read posts on Liberty Street Economics analyzed aspects of these issues. Read on to see how the restoration of student loan data to credit reports affected borrowers’ credit scores, whether the costs of a college degree are still worth it, how businesses are responding to higher tariffs, and why the U.S. runs a trade deficit.

America’s Military Is Back

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —As we close out 2025, the Trump Administration has racked up many big wins. But none are as significant as what President Trump and Secretary of War Hegseth have done to repair the recruitment crisis that took place during President Biden’s watch.

When I served in the House of Representatives, I chaired the Military Personnel Subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee, so I saw firsthand how bad things got under Biden, especially at the Pentagon and in our military.

When Biden was president, he presided over the worst recruitment crisis since our military became an all-volunteer force over 50 years ago.

In 2022, the Army set a goal to recruit 60,000 new soldiers, but it only managed to recruit 45,000. That’s 15,000 soldiers short. And the same thing happened again the following year, when the Army was again 15,000 soldiers short of its 65,000 recruitment goal. When you add up the recruitment losses under President Biden between 2021 and 2025, the Army shrank by 40,000 soldiers due to a lack of recruits. That’s as many as four divisions of troops.

The Navy fared no better. In 2023, it was 7,500 sailors short of its recruitment goal of 37,000. In 2024, it was nearly 5,000 short of its goal of over 40,000 new sailors. So between 2021 and 2025, the Navy shrank by 16,000 sailors, which is about three aircraft carriers’ worth of United States sailors.

That’s how bad the recruitment crisis got during Joe Biden’s watch.

The Murder of Charlie Kirk

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —The assassins who conspired against Julius Caesar could have stabbed their victim in the street, but they chose to commit their crime in the Curia of Pompey while the Senate was in session. The location’s symbolism was part of the message they intended to send. Charlie Kirk was assassinated on a college campus with a microphone in his hand as he answered questions from the crowd. It was the style of debate that earned him the love of millions and the admiration of many powerful figures, including the president of the United States. It was also the activity that led his murderer to mark him as someone who “spreads too much hate” and therefore deserved to die.

Charlie Kirk was a once-in-a-century talent who will not be replaced. He had boundless energy, acute judgment, and a capacity to evolve that was unusual in a public figure. His organization, Turning Point USA (TPUSA), and its political affiliate, Turning Point Action, managed a turnout operation for President Donald Trump’s 2024 presidential campaign that helped achieve the biggest popular-vote victory in a generation. Kirk himself could have been on a presidential ticket someday, possibly even the first ticket for which he would have been eligible. Had he lived, he would have turned 35 a month before the 2028 election.

Renters thousands of dollars out of pocket by Christmas

— Organisation: Everybody's Home —Confronting new analysis reveals renters in some of Australia’s capital cities are thousands of dollars worse off this Christmas compared to last, with Sydneysiders facing an extra $3,770 in rent annually.

Everybody’s Home has analysed SQM Research data on weekly asking rents to find the annual increase in rents from December 2024 to December 2025 across capital cities.

The analysis reveals renters in Sydney are paying an extra $72.50 per week to rent a house this year compared to last year, adding up to $3,770 extra annually, while unit renters face an additional $2,109.

Brisbane renters are paying $2,839 extra annually for a house, while renters in Perth are facing an additional $2,639.

On average across the capital cities, renters are paying $2,567 more annually to rent a house compared to last year, and an additional $1,823 to rent a unit.

The only capital city that is bucking the trend is Canberra where rent caps have kept increases significantly lower – just $0.79 extra per week to rent a house this Christmas compared to last.

Rent increases for units and houses