The American Mind Podcast: The Roundtable Episode 306

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —The American Mind’s ‘Editorial Roundtable’ podcast is a weekly conversation with Ryan Williams, Spencer Klavan, and Mike Sabo devoted to uncovering the ideas and principles that drive American political life. Stream here or download from your favorite podcast host.

The Trump Tariffs Go to Court | The Roundtable Ep. 306

State Troopers Laughed at the Suffering of People They Detained

— —Targeted tax cuts for battlers could be funded by taxing gas exports – new report

— Organisation: The Australia Institute —The LITO is an automatic tax refund – currently capped at $700 per year – which low-income earners receive when they lodge their tax returns.

Increasing the cap to $3000 would ensure the nation’s lowest-income earners stay ahead of inflation. Those earning between $32,000 and $46,000 would receive a tax cut of more than $2,000 per year.

The reforms would help those who’ve been hit hardest by inflation: workers and families whose nominal wages may have risen, but whose real wages have fallen, as a result of surging prices, particularly on essentials like food, energy and rent.

The analysis shows the cost of increasing the LITO would be $11.98 billion per year. This revenue could be replaced with a gas export tax – as suggested by the ACTU – which could raise $17 billion.

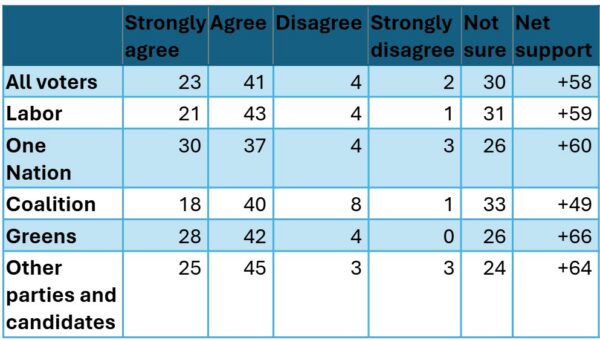

Recent polling also shows widespread support across party lines for a 25% tax on gas exports, with particularly strong support among One Nation and Greens voters.

One Nation yesterday announced a policy to charge the gas industry royalties, while Independent Senator David Pocock threw his support behind a 25% gas export tax.

“This is the engine room of the cost-of-living crisis – the current tax settings mean that Australian families on low incomes are not keeping up with price rises,” said Dr Richard Denniss, co-CEO of The Australia Institute.

“On the brink of extinction”: Niki Savva on the modern Liberal Party

— Organisation: The Australia Institute —On this episode of Follow the Money, journalist and author Niki Savva and Australia Institute co-Chief Executive Officer Dr Richard Denniss join Amy Remeikis to discuss how the Liberal Party ended up with their worst federal election result in modern history in 2025, why there’s no such thing as a safe seat in Australian politics anymore, and Niki’s latest book, Earthquake: the election that shook Australia.

This episode was recorded live at the Australia Institute’s Politics in the Pub in Canberra on Wednesday 18 February 2026.

What we owe the water: It’s time for a fossil fuel treaty by Kumi Naidoo is available now for just $19.95. Use the code ‘PODVP’ at checkout to get free shipping.

You can also subscribe to the Vantage Point series to get four essays a year on some of the most pressing issues facing Australia and the world.

Guest: Niki Savva, journalist, author and former political advisor

Guest: Richard Denniss, co-Chief Executive Officer, the Australia Institute // @richarddenniss

Estimating the Term Structure of Corporate Bond Risk Premia

— Organisation: Federal Reserve Bank of New York — Publication: Liberty Street Economics —The Suicidal Folly of a War with Iran [VIDEO]

— —Full Text:

The Laurel and Hardy negotiating team of Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner, coupled with Trump’s appalling ignorance of world affairs and megalomania, seem set to push the U.S. into yet another debacle in the Middle East, one the Congress has not approved, and the public does not want.

The demands imposed on Iran by the Trump White House are no more acceptable to the regime in Tehran than those imposed on Hamas in Gaza under Trump’s sham peace plan.

The Tariff Wears Two Hats: What the SCOTUS Majority Overlooked

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —On the question of President Trump’s emergency tariffs, the Supreme Court has spoken. In the Court’s view, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) does not authorize the president to impose tariffs during a declared emergency, namely, the massive trade deficits that threaten our economic security.

But the Court’s decision in Learning Resources, Inc. v. Trump was highly fractured. Only three justices—Kagan, Sotomayor, and Jackson—held that the law, under normal principles of statutory construction, does not give the president authority to impose tariffs. Justice Kavanaugh’s dissent, joined by Justices Thomas and Alito, quite persuasively demonstrates why that is not the case. As Justice Thomas noted in his separate dissent, the power to “regulate…importation” has throughout American history “been understood to include the authority to impose duties on imports.”

The other three justices who formed the majority holding—Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Gorsuch and Barrett—resorted to the major questions doctrine. This principle of statutory interpretation holds that Congress must speak with super clarity on issues of “economic and political significance” for the Court to approve a delegation to the executive. The turn to the major questions doctrine implies that the statute, under normal principles of statutory construction, authorizes the president’s action, a point that Justice Gorsuch explicitly conceded in his concurring opinion.

The Predatory Hegemon (w/ Stephen Walt) | The Chris Hedges Report

— —This interview is also available on podcast platforms and Rumble.

As Donald Trump’s administration continues down the path of self destruction, it is taking the rest of the American population down with it. The abandonment of international allies, treaties and norms, the political scientist Stephen Walt argues, will slowly ostracize the United States and give rise to a multipolar world order which will leave the country behind.

Walt, the Robert and Renee Belfer Professor of International Affairs at the Harvard Kennedy School and author of multiple books, joins host Chris Hedges on this episode of The Chris Hedges Report to chronicle what this decline may look like and how Trump’s policy choices are not unlike past empires in history.

Carbon conference more about capturing taxpayer dollars than emissions

— Organisation: The Australia Institute —For more than a decade, Australia Institute research has shown that CCS is one of the biggest and most expensive failures in the history of climate policy in Australia.

The research shows that CCS projects have repeatedly missed deadlines, fallen monumentally short of carbon capture targets and gobbled up billions of taxpayer dollars.

Sadly, detailed analysis of all the available evidence suggests there is little likelihood the epic failure of CCS will change any time soon.

“The gas export industry already gets most of its gas for free. This conference is gas companies saying they want publicly-subsidised infrastructure as well,” said Rod Campbell, Research Director at The Australia Institute.

“It’s clear that this conference is about helping the gas industry, not about helping the climate. Look at who is attending: all the gas companies and none of the climate organisations.

“Carbon capture projects aren’t meant to work. 100% of carbon capture projects on gas-fired power stations have failed. On coal-fired power stations, the rate is 98%.

“It isn’t supposed to work, it is supposed to let investors pour money into new gas projects while pointing at spending on carbon capture to avoid any criticism on climate.

“Gas companies don’t want to pay for carbon capture themselves, they want taxpayers to pay.

“In 2024, a $700 million carbon capture lobby group told its industry donors to stop giving it money; that it had more money than it could spend.

We Need Friends, Not Flatterers

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —Marco Rubio’s speech at the Munich Security Conference may have been enough for Munich 2026 to displace Munich 1938 in the annals of geopolitics. Far more than an effective rehearsal of European and American commonalities, it touched on the very soul of politics.

Running through Rubio’s speech was a metaphor of filiation: “For us Americans, our home may be in the Western Hemisphere, but we will always be a child of Europe.” But sons and fathers do sometimes part ways, and skeptics in Europe have seen Rubio’s words as window dressing on hostility. Just a month ago, President Trump’s push to compel Denmark to cede Greenland climaxed in another, harsher speech from a glamorous podium. The American postures at Davos and at Munich, however, must be seen as reflecting an underlying commitment to forging a frank friendship with Europe.

Evidently, America’s bond with Britain and France is different in kind from her arrangements with Saudi Arabia or Mongolia. Sharing common enemies is not the same as participation in common goods, which the Trump Administration is working to articulate.

AnnouncementCall for Submissions : Treasury Historical Association’s 1500 Penn Prize

— Organisation: Just Money — Deadline to apply : March 13, 2026

More “Announcement

Call for Submissions : Treasury Historical Association’s 1500 Penn Prize”

Speech: Recent Developments in Inflation and the Economic Outlook

— Organisation: Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) —The Mar-a-Lago model: how Trump is trying to dominate global governance

— Organisation: The Australia Institute —On this episode of After America, Allan Behm joins Dr Emma Shortis to discuss the potential consequences if the United States again strikes Iran, the first meeting of Trump’s grotesque ‘board of peace’, and the striking similarities between a(nother) shamefully racist week in Australian politics and Trump administration rhetoric and policies.

This discussion was recorded on Friday 20 February 2026.

The latest Vantage Point essay, What we owe the water: It’s time for a fossil fuel treaty by Kumi Naidoo, is available now for $19.95. Use the code ‘PODVP’ at checkout to get free shipping.

Guest: Allan Behm, Advisor, International & Security Affairs, the Australia Institute

Host: Emma Shortis, Director, International & Security Affairs, the Australia Institute // @emmashortis

Show notes:

Shorter America this week: Will he or won’t he on Iran; The Trump doctrine?; On climate, he absolutely will; The only thing more powerful than hate is love by Emma Shortis, The Point (February 2026)

Defending Trump’s Latin America Policy

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —A common argument against the Trump Administration’s policy in South America is that it will inevitably drive the region toward China. But for the most part so far, the opposite appears to be true.

American presidents including John Quincy Adams, both Roosevelts, John F. Kennedy, and Ronald Reagan understood that the United States cannot successfully compete overseas if it neglects its own backyard. These presidents all invoked the Monroe Doctrine (and in Adams’s case, wrote it), indicating that Washington would view any new great-power incursions into the Western Hemisphere as a hostile act.

Over a period of some 12 years, the Obama-Biden approach was the opposite: they explicitly dismissed the Monroe Doctrine and neglected U.S. security concerns in Latin America while Beijing’s influence advanced. They looked to appease left-wing dictatorships, including Cuba and Venezuela, and deferred to a liberal guilt complex regarding America’s supposedly awful Cold War policies in the region. Thankfully, that approach is now over.

The 2025 U.S. National Security Strategy and 2026 National Defense Strategy both make it very clear that hemispheric defense is among this administration’s highest priorities. That is as it should be. The first Trump Administration’s Latin America policy was a major improvement over Obama’s, and the second Trump Administration is a major improvement over Biden’s.

RBA Must Not Repeat its Post-COVID Errors

— Publication: Progress in Political Economy —Inflation took a surprising and unwelcome jump in Australia in the final months of 2025. After peaking at almost 8% year-over-year in late 2022, inflation rapidly declined – reflecting both the repair of supply chains after the pandemic, and the chilling effects of 13 interest rate hikes from the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). Within two years, by end-2024, inflation had fallen back below the RBA’s 2.5% target.

The RBA then began to cut rates, but more slowly than most other global central banks: just three cuts in 2025, for a total of 0.75 percentage points. Those cuts supported a modest pickup in economic activity. But with GDP growth of barely 2% last year, employment growing just 1%, and official unemployment above 4%, it’s not credible to claim the economy is running ‘hot’.

Déjà vu All Over Again

Now, after the surprise jump in inflation at end-2025, the RBA is reversing course. Year-over-year growth in the Consumer Price Index accelerated to 3.8% in December. The RBA responded quickly with a quarter-point rate hike on 4 February, taking the cash rate target back up to 3.85% (one of the highest among major industrial economies). Weary Australians fear the start of another painful episode of rising debt charges, unaffordable mortgages, and job insecurity.

What’s gone wrong in the battle to stabilize inflation in Australia? And can the problem be solved by the RBA once again pulling out its big interest rate hammer?

Social housing push dominates CGT discount inquiry as hearings kick off

— Organisation: Everybody's Home —Social housing has emerged as a top priority for capital gains tax reform, with half of all organisation submissions to a Senate inquiry backing or raising the idea of redirecting the billions in savings toward building affordable rentals.

Ahead of hearings kicking off today, Everybody’s Home has analysed the submissions and found that more than seven in 10 organisations want the investor tax break to be abolished or reformed.

The hearings will be held in Melbourne today, followed by Canberra and Sydney later this week.

Everybody’s Home spokesperson Maiy Azize said: “These responses show strong support for winding back tax breaks that reward property investors while renters fall further behind.

“The capital gains tax discount is unfair, and it’s making the housing crisis worse. It lines the pockets of investors and pushes up the cost of homes, benefiting people on the highest incomes. It is locking everyday people out of homes they can afford.

“Experts, community organisations and frontline services across the country see the impact of these tax breaks every day. When more than seven in ten groups tell the Senate this tax break should go or be wound back, the message couldn’t be clearer.

“People want tax reform that actually makes homes more affordable. Many of the organisations backing change want the savings to be used to build more public and community homes – rentals that people can actually afford.

Chris Hedges Live Documentary Q&A TODAY: Forging a New Movement for Palestine in Italy

— —Questions will be taken from the comment section of this Substack post, as well as during the livestream on YouTube/X. Please attempt to keep your questions direct and relatively brief, as I cannot read entire paragraphs during the show.

Sri Lanka's 17th IMF Debt Trap

— —Since 2022, Sri Lanka has been struggling with the worst debt crisis in the country’s history due to a substantial decline in foreign exchange revenues from tourism, remittances, and exports. I wrote about it back then in The Lens (Stephanie Kelton’s substack). The debt crisis forced the country to agree to the 17th IMF intervention since 1965 with one of the most aggressive austerity programs in the country’s history. If we track IMF interventions in Sri Lanka, the record shows that the IMF intervened in Sri Lanka once every 3 years on average to dictate the country’s domestic economic policy choices.

Resistance101: Forging a New Movement for Palestine in Italy DOCUMENTARY

— —Joing us for a livestream where we will discuss the movie at 3pm ET here!

With little hope of the genocide in Gaza subsiding, dock workers in major Italian port cities have organized strikes and large demonstrations to halt arms shipments to Israel. These actions are a direct response to the refusal of international institutions and governments around the world to confront the carnage. Though the genocide continues, the dockworkers’ industrial disruption offer us a model of resistance. Will the Italian way spread to the imperial core — and can it end the genocide?

The Suicidal Folly of a War with Iran

— —Fake Data, Upcoming Book, and the Political Economy of AI

— —

The world is on fire - and I've often been at a loss for how to constructively contribute to public discourse. For decades, I have shared knowledge gained through fieldwork to offer a different perspective on complex sociotechnical matters. Too often these days, I find myself banging my head against the wall while navigating the cacophony of anguish that is emerging in all directions. For better or worse, I chose this time to turn my attention locally. I have found joy trying to find my footing as a professor and think more directly about how to prepare the next generation. And amidst it all, I've also had a series of wins, which I thought I'd share.

Are We Finally Breaking Out — Or Setting Up for One More Leg Lower?

— Organisation: Applied MMT —

Over the past five months, the S&P 500 has gone essentially nowhere.

Yes, we’ve made marginal new highs. Yes, we’ve had bursts of volatility. But zoom out and what you see is a market stuck in sideways consolidation dating back to early October. The S&P is up barely 1–1.5% over that stretch. The Nasdaq is actually down slightly.

So the real question is:

Are we building pressure for a sustained breakout — or setting up for another leg lower first?

To answer that, we have to step away from the noise and focus on what actually drives price.

And if you’ve followed my work for any amount of time, you know exactly where this is going:

Flows.

Markets Follow Flows — Not Narratives

Heading into Q4 of last year, I laid out the case that we were likely to see volatility increase. Why?

Because underlying fiscal flows were slowing down.

That deterioration in flows — partly tied to tariff dynamics earlier in 2025 — suggested we were entering a weaker liquidity backdrop. We did get volatility, but instead of a dramatic selloff, we’ve largely just gone sideways.

That part has played out exactly as expected:

Refuting the Media’s Latest Immigration Propaganda

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —The corporate media recently obtained a leaked Department of Homeland Security (DHS) memorandum changing the agency’s policy on forcibly entering the home of an alien who has been ordered to be deported by an immigration judge. Discussions of the Minneapolis protests eclipsed coverage of the memo, but as one might expect, the chattering class has been experiencing a slow-motion meltdown over DHS taking immigration enforcement seriously.

According to the talking heads, civil rights in the United States will now evaporate. We can look forward to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents busting into our homes to arrest us for removing the tag on our mattresses that says, “Do Not Remove by Law.”

However, such claims are utter nonsense. They are premised on the media’s deceptive implication that ICE is deliberately depriving aliens of due process. But the fact is, 99% of the claims currently circulating in the media regarding aliens and judicial warrants are prime examples of what U.S. Army Lieutenant General Russel Honoré famously referred to as “stuck on stupid.”

Resistance 101 Documentary Trailer (COMING FEB. 21)

— —Correction: The trailer above advertises our scheduled livestream Q&A on the documentary as being on Feb. 21 at 7pm ET — we have changed the livestream to be on Feb. 21 (same day) at 3pm ET. Apologies for the inconvenience, and thank you for understanding.

With little hope of the genocide in Gaza subsiding, dock workers in major Italian port cities have organized strikes and large demonstrations to halt arms shipments to Israel. These actions are a direct response to the refusal of international institutions and governments around the world to confront the carnage. Though the genocide continues, the dockworkers’ industrial disruption offer us a model of resistance. Will the Italian way spread to the imperial core — and can it end the genocide?

How Inequality Creates Insecurity | Between the Lines

— Organisation: The Australia Institute —The Wrap with Dr Emma Shortis

More often than not, Australia’s relationship with the United States highlights and reinforces the worst in our politics, and the worst in theirs.

Here at home, the week began with some shamefully racist politicking by federal parliamentarians. A “hardline” Liberal Party immigration proposal was “leaked” to the Australian media. Straight from the Trump playbook, the proposal mooted banning immigrants from 37 regions, deporting 100,000 asylum seekers and visa holders, and even vetting the social media of aspiring migrants. To followers of American politics, that might sound very familiar.

Photo: AAP Image/Bianca De Marchi

What Workplace Composition Are Job Candidates Looking For?

— Organisation: Federal Reserve Bank of New York — Publication: Liberty Street Economics —

Why do workers still segregate by sex across occupations, industries, and firms? Recent research has focused on how preferences for job amenities, like flexibility, may differ by sex. However, one “amenity” that has received relatively little attention is the sex composition of a job itself. In a recent paper, I conducted a survey experiment to estimate men’s and women’s preferences for sex composition in the workplace. One result is that women and young single men prefer jobs with at least half female coworkers.

The Problem of the Veto State

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —The Senate’s failure to pass the SAVE Act, which would require documentary proof of citizenship to vote in federal elections, is a testament to the power of the managerial regime. The bill does not attempt to remake the constitutional order, abolish federalism, or nationalize election administration in any comprehensive sense. It addresses a narrower, more elemental question: whether the American people, acting through their representatives, may insist that those who vote in American elections are in fact American citizens. The answer under the present regime appears to be no.

This is one more instance of a now-familiar pattern: the American people express a preference through elections, their representatives assemble a legislative response, and the legislature proves incapable of translating that preference into law. The constitutional machine, once praised for its capacity to refine and elevate popular judgment through its aristocratic elements, now increasingly appears to dissolve judgment altogether into a diffuse and unaccountable veto.

What is a republic (in the classical sense) if it cannot act on matters essential to its own political existence? And what becomes of constitutional forms when the ends for which they were designed can no longer be secured through them?

The Mixed Regime and Its Assumptions

The American Mind Podcast: The Roundtable Episode 305

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —The American Mind’s ‘Editorial Roundtable’ podcast is a weekly conversation with Ryan Williams, Spencer Klavan, and Mike Sabo devoted to uncovering the ideas and principles that drive American political life. Stream here or download from your favorite podcast host.

Rubio Looks to the West | The Roundtable Ep. 305

Following on from J.D. Vance’s bracing speech in 2025, Secretary of State Marco Rubio called on European allies to resist the managed decline of the West at the 2026 Munich Security Conference this week. The welfare state is a slow moving trainwreck. Appeasement of climate cultists stunts economies. Mass migration threatens to disrupt our civilization. Playing good cop to the VP’s bad cop, Rubio outlined America’s vision to revive the spirit and strength of the shared Western project. Plus: The guys discuss the Left’s compassion fatigue, Hungary’s coming election, and the legacy of the late Dr. Mickey Gene Craig: teacher, mentor, and friend.

Is ICE Opening a Detention Center in Lebanon?

— —Real wages are down, but apparently inflation is all your fault

— Organisation: The Australia Institute —On this episode of Dollars & Sense, Greg and Angus discuss why Coles is in court over its pricing, whether it’s time to panic with government debt set to hit $1 trillion, and the role of corporate profits in driving inflation.

This discussion was recorded on Wednesday 18 February 2026.

What we owe the water: It’s time for a fossil fuel treaty by Kumi Naidoo, is available now for just $19.95. Use the code ‘PODVP’ at checkout to get free shipping.

You can also subscribe to the Vantage Point series to get four essays a year on some of the most pressing issues facing Australia and the world.

Host: Greg Jericho, Chief Economist, the Australia Institute // @grogsgamut

Host: Angus Blackman, Executive Producer, the Australia Institute // @angusrb

Show notes:

What Will Replace the Old Order?

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —The pivotal question of what will follow the crack-up of the liberal international order dominated the highest levels of European politics last week.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio gave his own, forceful answer at the 2026 Munich Security Conference. Following Vice President JD Vance’s provocative speech last year, Rubio delivered an equally spirited address that issued an ultimatum: rationalizing collapse and weakness is no longer the policy of the United States—and it should no longer be Europe’s policy either. America has no “interest in being polite and orderly caretakers of the West’s managed decline,” he stated forthrightly.

Instead, Rubio urged a reformation of the “global institutions of the old order” to defend and strengthen the key pillars of Western civilization.

Social Democrats of the North: League for Social Reconstruction

— Publication: Perspectives Journal —Listen to the full conversation on the Perspectives Journal podcast, available to subscribe on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, YouTube, Amazon Music, and all other major podcast platforms.

Release of Guidance for the Australian Clearing and Settlement Facility Resolution Regime

— Organisation: Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) —Media Release: Free Palestine Melbourne launches campaign demanding release of Palestinian leader Marwan Barghouti from Israeli prison

— Organisation: Free Palestine Melbourne —One Nation and Greens voters strongly support 25% Gas Export Tax: poll

— Organisation: The Australia Institute —The results show that support for taxing gas export cuts across party lines, including among voters often seen at opposite ends of the political spectrum, such as the Greens and One Nation.

Australia Institute research shows a 25 per cent tax on gas exports could raise $17 billion every year, while incentivising producers to prioritise the supply of gas to domestic customers.

The findings come ahead of the upcoming Farrer by-election, expected to be contested by the Liberals, Nationals, Pauline Hanson’s One Nation, and independent candidates.

Statement: “Gas export corporations should pay a flat 25% tax on gas exports”

“Australia is one of the world’s largest exporters of liquefied natural gas,” said Dr Richard Denniss, co-CEO of The Australia Institute.

Shipwreck on Zombie Road

— —There is a shipwreck at the end of Zombie Road. I walked miles to see it: past moss-covered cliffs and century-old railroad tracks half-buried in the earth. I hadn’t hiked Zombie Road since 2022, when an elderly woman I used to pass on the trail disappeared. I didn’t know her name, but I knew her smile. When she went missing, I checked the news round the clock, hoping she would be found. Her face is on a memorial bench now. I put a flower there.

I finally felt ready to return to Zombie Road. 2026 leaves you ready for everything and nothing. I live in a nightmare echo chamber where topics I covered for over a decade in my books and articles — autocracy, institutional complicity, extremely specific details of the Epstein/Maxwell case — are now repeated by the same pundits and officials who dismissed them when it mattered most. They buried crimes in silence, then noise, and now spectacle.

The lack of accountability stays the same.

How Liberal Education Can Aid America’s Renewal

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —As America approaches its semiquincentennial, a surprising trend offers profound hope for the nation’s renewal: young Americans are returning to church. If you are like me and have noticed week by week more younger attendees and far fewer gray heads in your house of worship, this is anecdotal confirmation that change is afoot.

Recent data from the Barna Group reveals that Millennials and Gen Z are leading a resurgence in church attendance, with younger generations attending nearly two weekends per month on average in 2025—up significantly from just over one in 2020. Young men in particular are driving this shift, with higher weekly attendance rates than women for the first time in decades. This marks a historic generational reversal, as younger adults outpace older cohorts in frequency of worship.

Ensuring That Trump’s Triumph in Venezuela Doesn’t End in Tragedy, Pt. I

— Organisation: The Claremont Institute —The Venezuelan strongman Nicolás Maduro and his equally despotic wife are under lock and key in a New York prison, living embodiments of President Trump’s revivification of the Monroe Doctrine. Maduro, the chosen successor of the demagogic leftist tyrant Hugo Chávez, presided over a gangster regime that had reduced its people to hunger and penury, driving a third of Venezuela’s 24 million citizens into exile. Maduro’s regime maintained power through stolen elections, the machinations of the Cuban secret police, and active collaboration with the most unsavory drug cartels.

For a time, Chávez’s so-called Bolivarian socialism bought off the poor with bread and circuses—that is, massive subsidies and assorted free goodies made possible by high oil prices. This was bolstered by the ideological illusions of leftist political elites and Hollywood stars, ranging from Jeremy Corbyn, Ken Livingstone, and Bernie Sanders to Danny Glover and Sean Penn, who saw another exotic socialist paradise and an avatar of social justice in the making. But over time the Chavista regime revealed itself as yet another nightmare scenario, where political liberty was confiscated, arbitrary power went unchallenged, and food was remarkably scarce. The war on the rich and the entrepreneurial middle classes always turns out to be a war on everyone, including the urban and rural poor.

Seeing Through the Shutdown’s Missing Inflation Data

— Organisation: Federal Reserve Bank of New York — Publication: Liberty Street Economics —The Increasing Attacks on Francesca Albanese Presage a New Dark Age

— —Full Text:

The vicious and sustained campaign mounted against Francesca Albanese, the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian Territory occupied since 1967, by Israel and the U.S. now includes the German, Italian, French, Austrian and Czech foreign ministers demanding her resignation. This campaign is part of an effort by industrial nations to at once sustain the genocide in Gaza — nearly 600 Palestinians have been killed in Gaza since the sham ceasefire took effect — and silence all those who demand the international community abide by the rule of law.

The latest assault on Francesca, part of a concerted effort to discredit international bodies such as the U.N., is based on a deliberately truncated video of a talk Francesca gave in Doha on February 7 that distorts and misconstrues her words. But truth, of course, is irrelevant. The goal is to silence her and all who stand up for Palestinian rights.